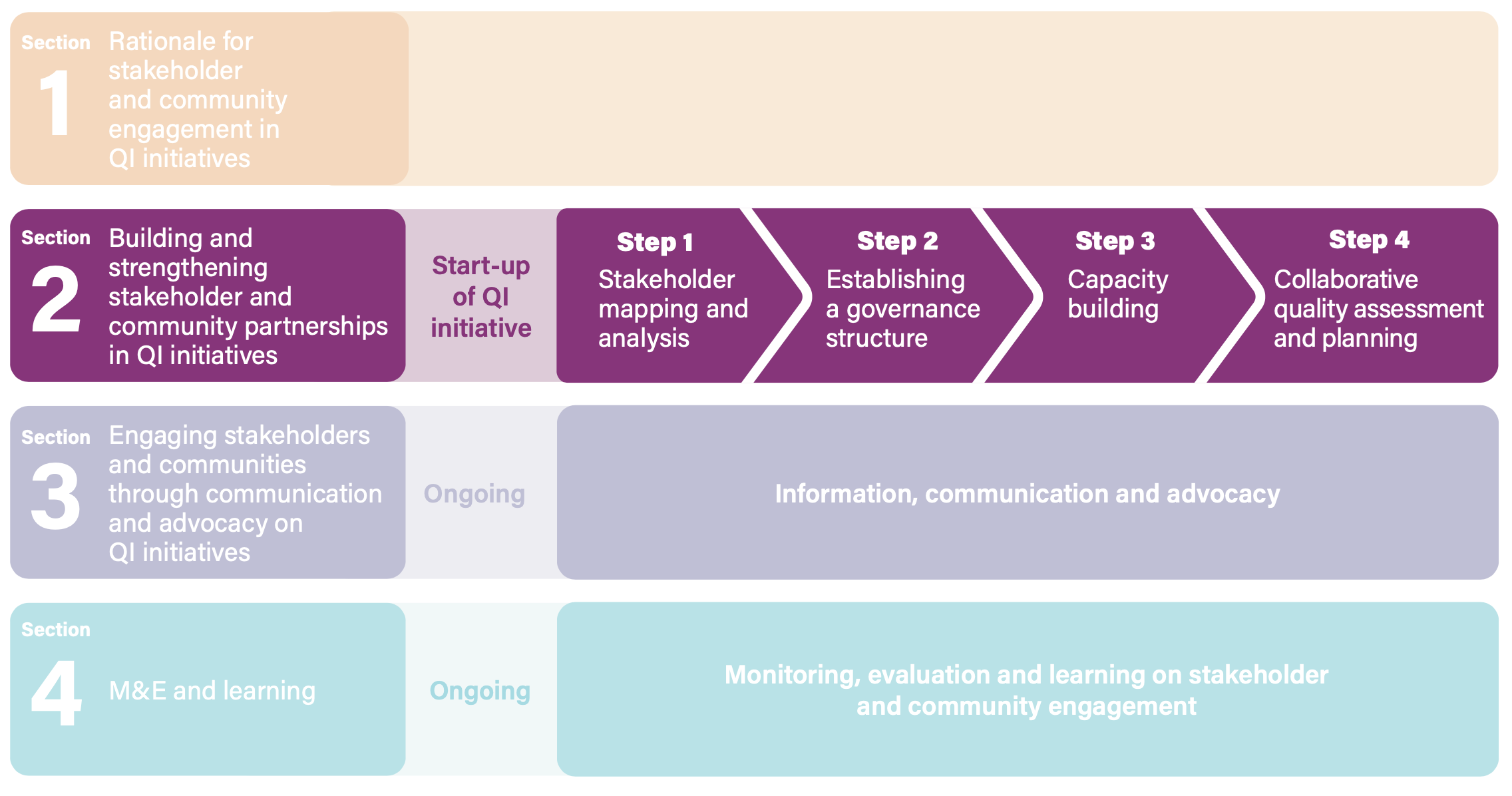

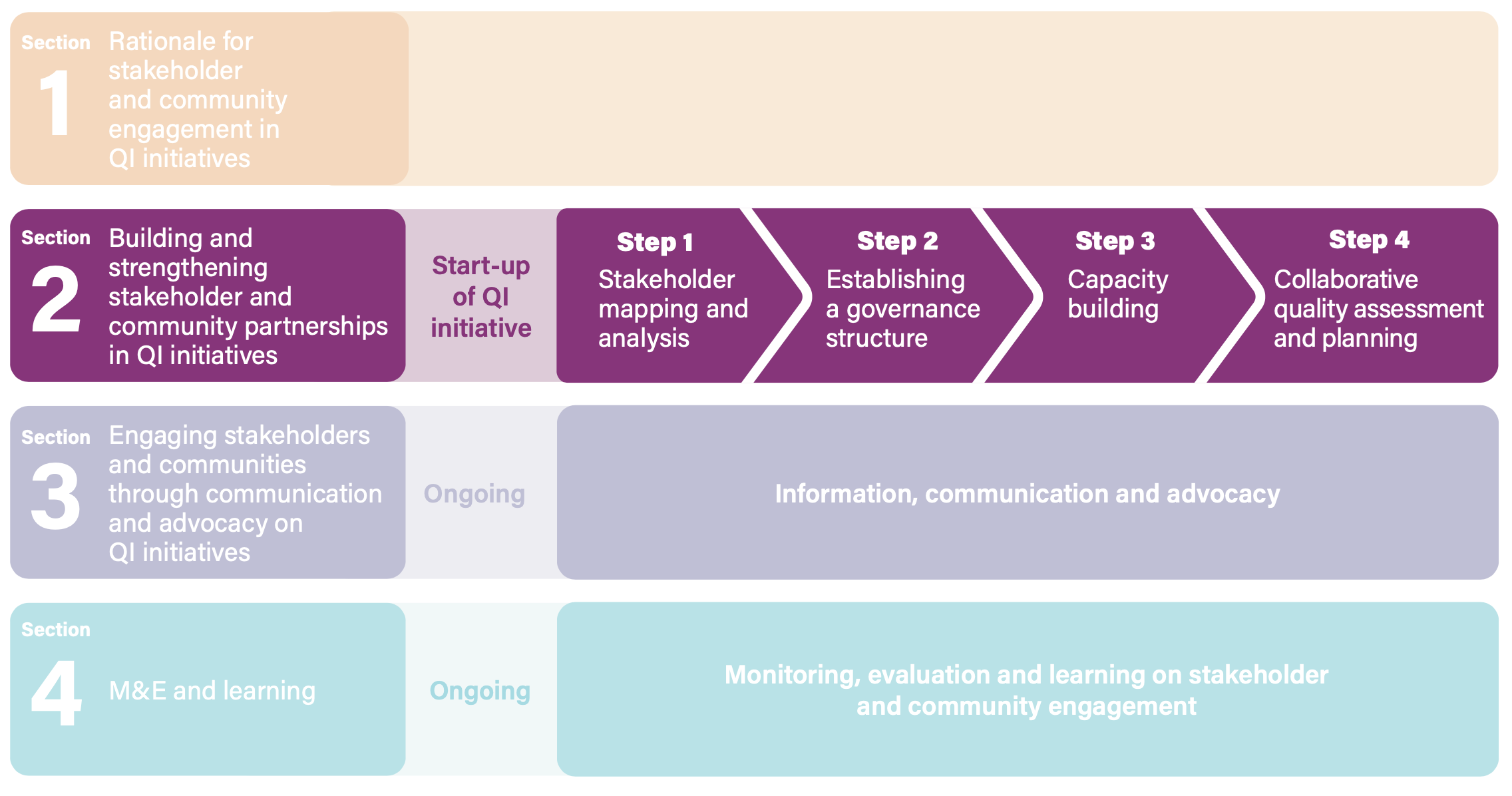

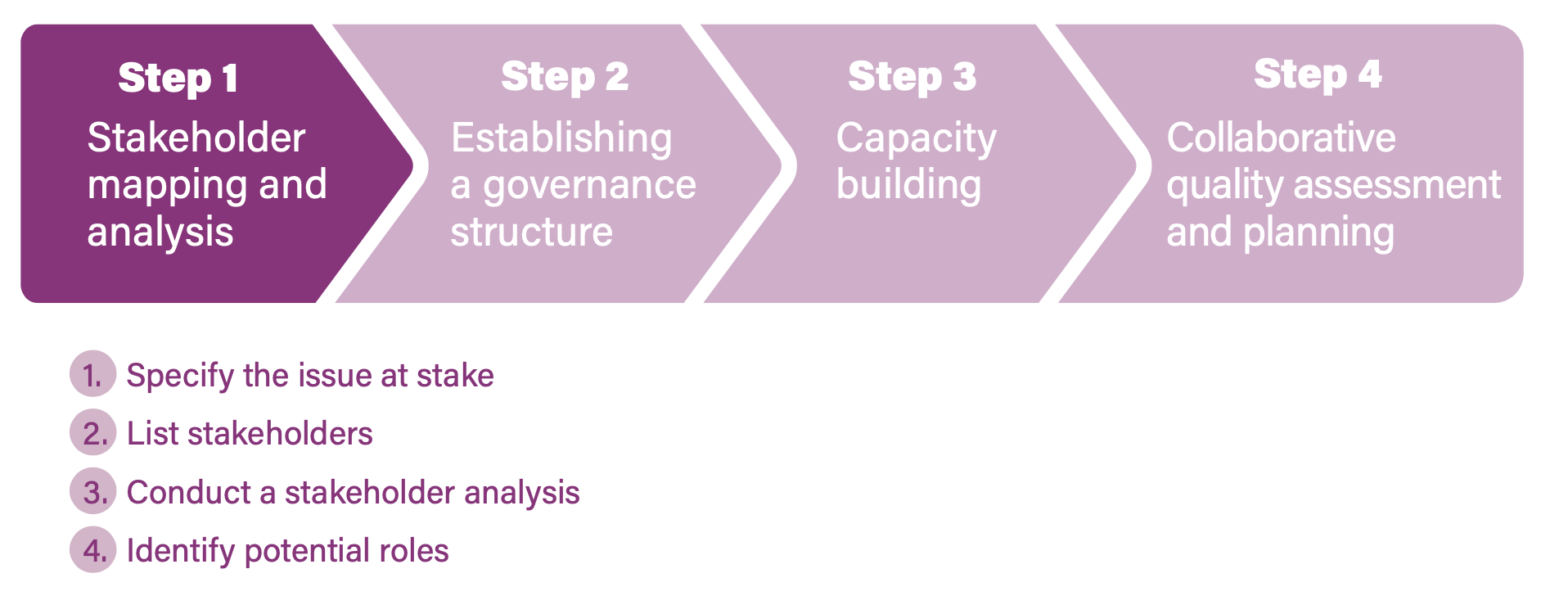

SECTION 2. BUILDING AND STRENGTHENING STAKEHOLDER AND COMMUNITY PARTNERSHIPS IN QUALITY IMPROVEMENT INITIATIVES

For QI initiatives to be effective, meaningful and sustainable, stakeholder and community engagement is crucial across the start-up and implementation phases and across the health-care system at the national, district and facility levels. This section outlines four steps to take, with corresponding activities relevant to each step. Engagement for policy-making, programming and service delivery should follow similar steps, though the types of stakeholders may vary by country and level. At the national level, for example, engagement will mostly refer to stakeholder groups relevant for that level, with users and communities being represented by intermediary structures such as civil society organizations. At the facility level, engagement may be with representatives too but also more directly with groups of women and community members, depending on the engagement approach. The approaches presented in this section will be common to all levels but include such specificities where relevant.

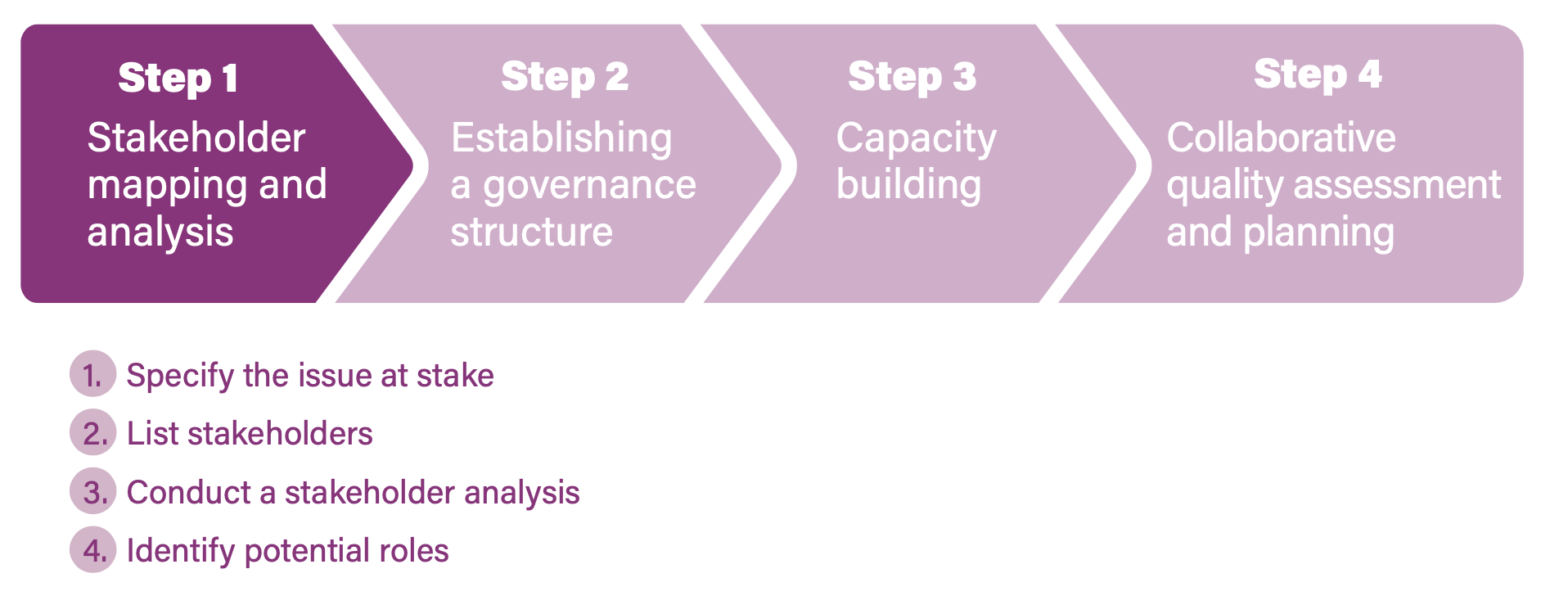

Step 1. Stakeholder mapping and analysis

Given the rationale outlined above, policy-makers and planners need to conduct a careful stakeholder mapping and analysis to ensure that the right individuals and organizations are contributing commitment, knowledge and resources to QI initiatives. Such mapping will take into account differences in stakeholders’ experiences, influence and power, and facilitate effective engagement. It also helps to define the roles that stakeholders can play in the programme, and the resources (information and knowledge, funding, technical assistance, alliances, advocacy) they can bring to bear. The result – a stakeholder engagement strategy – should be part of the QI initiative, strategies and operational plans.

Stakeholder mapping and analysis is often done informally, in an ad hoc way, and not systematically updated. As a result, it may only include stakeholders who already agree with the policy or programme or only invite participants from selected organizations that are directly involved in the implementation. Such approaches may miss important interest groups that could contribute valuable insights, influence or resources to the programme. Omitting their voices may threaten the embedding and sustainability of the programme. (27)

Stakeholder mapping and analysis is often done informally, in an ad hoc way, and not systematically updated. As a result, it may only include stakeholders who already agree with the policy or programme or only invite participants from selected organizations that are directly involved in the implementation. Such approaches may miss important interest groups that could contribute valuable insights, influence or resources to the programme. Omitting their voices may threaten the embedding and sustainability of the programme. (27)

Stakeholder mapping and analysis can be broken down into four activities. These can be tailored during any stage of the QI initiative (planning, implementation and M&E), although it is most beneficial at the early stages of programme design, prioritization and preparation. At that stage, a stakeholder analysis will avoid overlooking important or influential individuals or organizations.

Box 2 at the end of this section lists resources available to support stakeholder and community mapping and analysis.

Activity 1. Specific the quality issue at stake

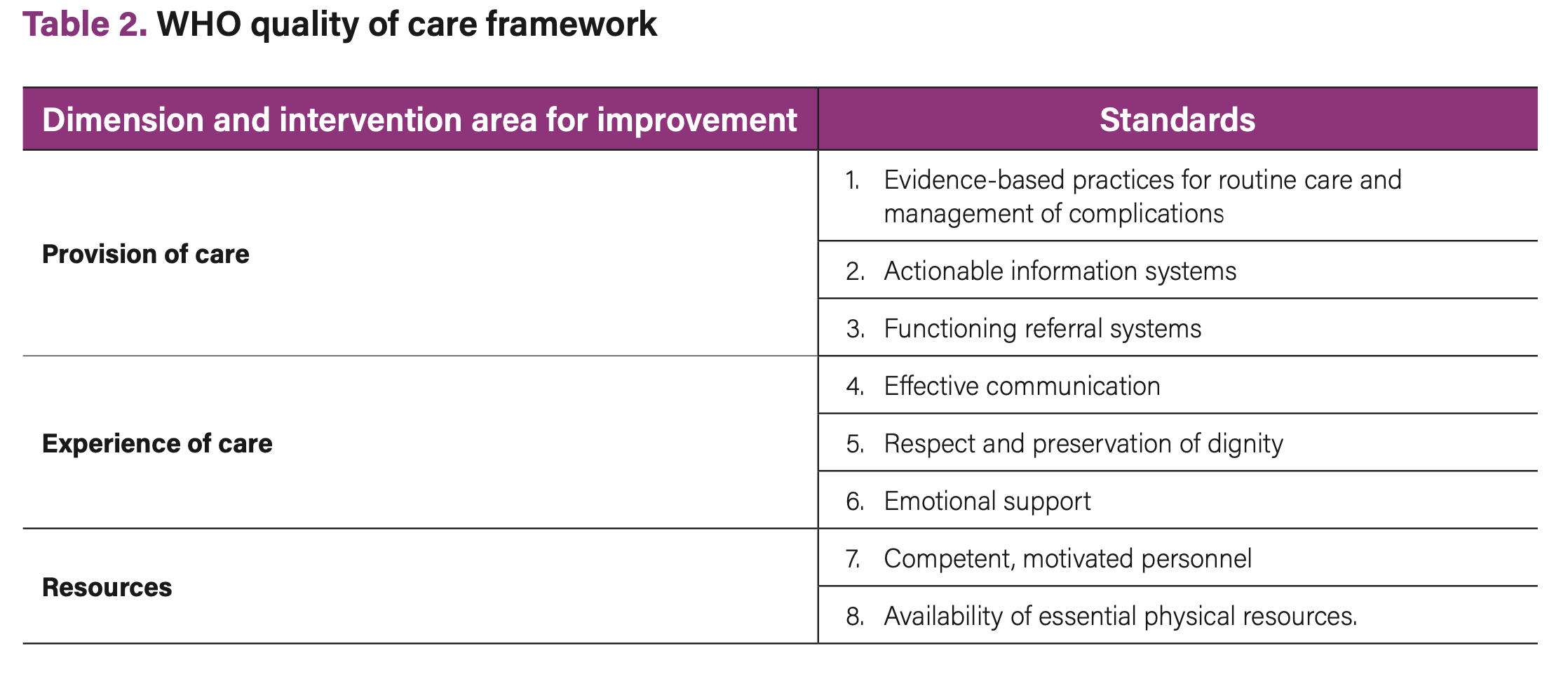

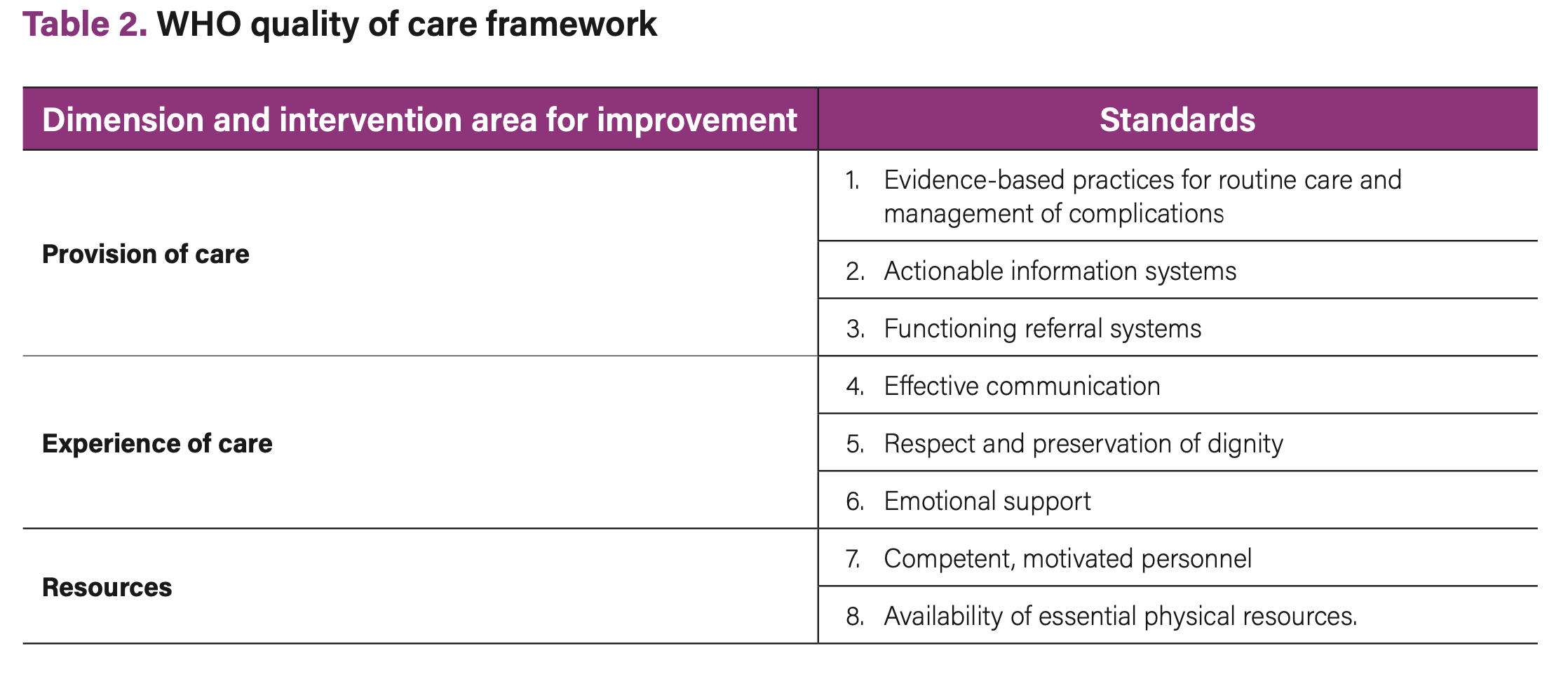

The issue or problem needs to be carefully delineated. If it is stated very broadly (“QoC in MNCH”), it will be hard to identify relevant stakeholders. It may be useful to break down the analysis; for example, by focusing on one QoC dimension or standard at a time (see Table 2) (28) or a quality issue that affects particular groups (e.g. adolescents or unmarried women or health workers in rural areas).

The quality issue at stake may be informed by existing quality assessments or may be predefined by the improvement aims set by national-level QoC policies. When there is an opportunity to conduct a new or more comprehensive (i.e. addressing all dimensions of QoC) quality assessment at national, district, or facility level, this could become a stakeholder and community engagement process in itself. Guidance on such processes is provided in Section 3.

The quality issue at stake may be informed by existing quality assessments or may be predefined by the improvement aims set by national-level QoC policies. When there is an opportunity to conduct a new or more comprehensive (i.e. addressing all dimensions of QoC) quality assessment at national, district, or facility level, this could become a stakeholder and community engagement process in itself. Guidance on such processes is provided in Section 3.

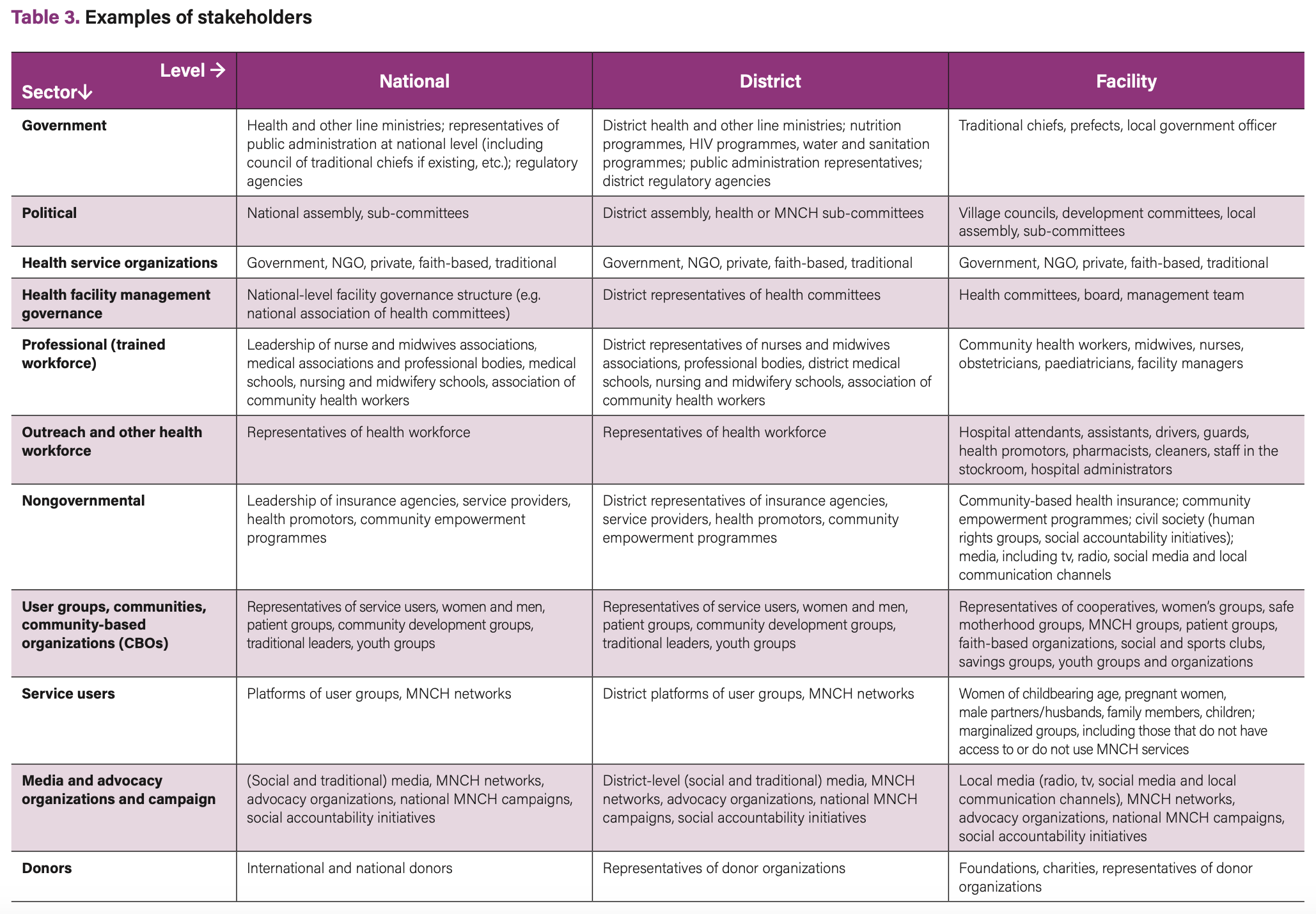

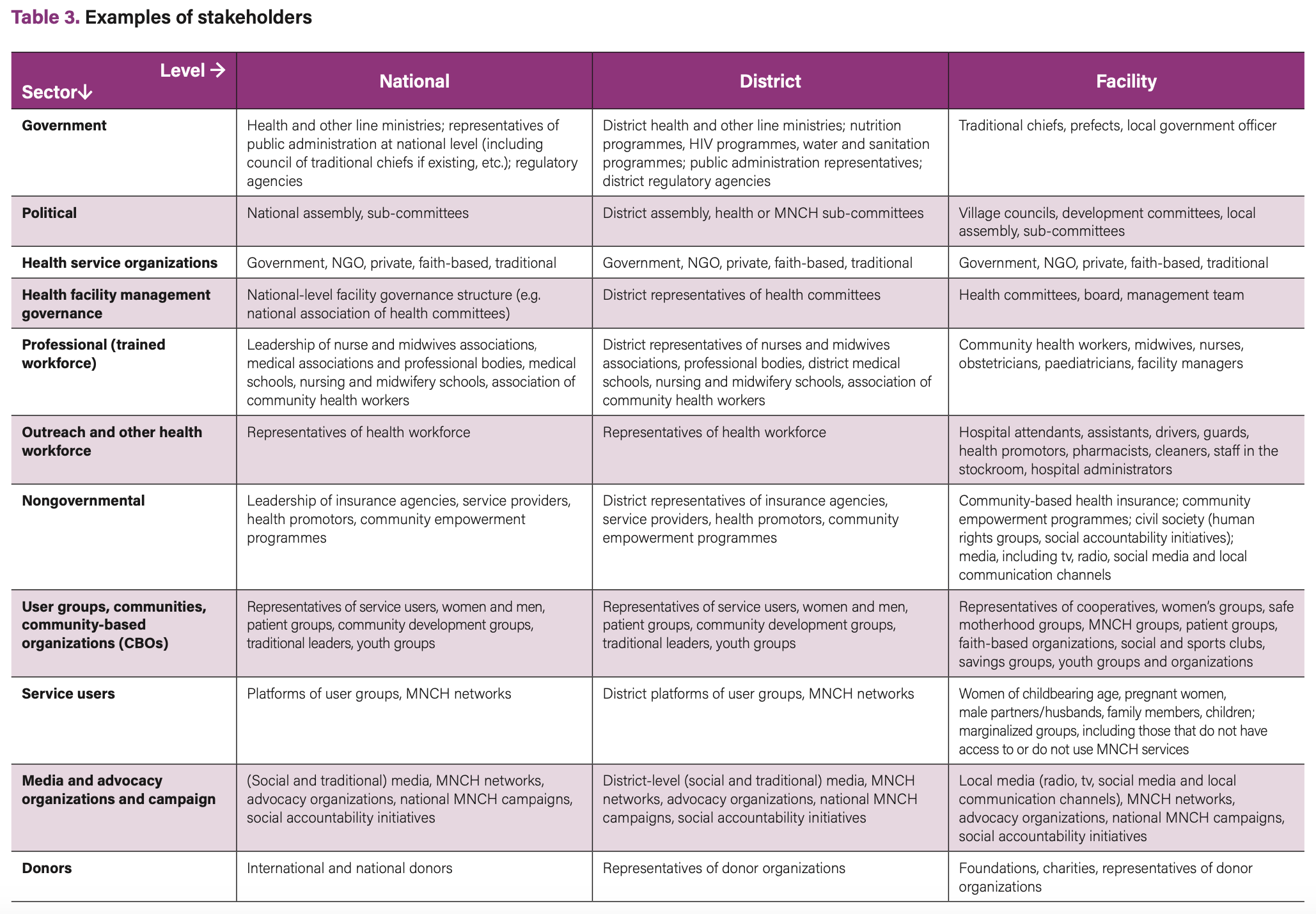

Activity 2. List the names of stakeholders relevant to the quality dimension at stake

These include persons; groups such as health professionals, councils or organizations; and research institutions with interests in the defined issue, quality gap or improvement programme, or who may be directly or indirectly affected by the process or outcome. List organizations, groups, or individuals and categorize them by their location (national, district, facility) and sector. Table 3 presents examples of stakeholders for different levels.

An obvious start may be to identify existing QI efforts and start with mapping stakeholders who have already been involved in these programmes. District offices are often well placed to map these, to identify gaps that need to be filled, and to avoid duplication. Good starting references may also be health governance and health systems policies.

Make sure to include stakeholders who are directly affected by QoC issues, including representatives of women using MNCH services and marginalized groups. Also include representatives of health providers, especially midwives and nurses, and managers through their professional associations or societies. Their voices and perspectives on quality of care and challenges and solutions as well as their support to the process is instrumental to the success or failure of any QI strategy. (29)

Activity 3. Conduct a stakeholder analysis. For each stakeholder identified, describe, per level, their stake in the QoC issue, namely:

- Experience with QI initiatives in MNCH. People who can bring in success factors, lessons learned from interventions or from challenges around QoC in MNCH. For example, those who have experience in:

- QoC policy-making, implementation, documentation and scale-up;

- QoC policy-making, implementation, documentation and scale-up;

- advocacy for improved QoC in MNCH or other sectors, such as adolescent care;

- creating an enabling environment for improved QoC in MNCH;

- community engagement;

- evaluating QoC and QI initiatives.

- Expertise and knowledge of the quality issue identified (e.g. people who have information about the challenges, about community structures and preferences, or information about stakeholders).

- Determine their level of interest and commitment (support or oppose; why).

- Distinguish between stakeholders with a short-term interest (e.g. in piloting the learning initiative) and those that can play a role in the scale-up of the intervention.

- Level of responsibility and accountability for QoC in MNCH (see guidance on mapping responsibilities). (30) National health governance policies can be used for this exercise. (31)

- Available resources (staff, funding, tools, information, influence in decision-making).

- Influence on other stakeholders: people whose opinions are respected and who have some influence over public and stakeholder opinion, and who can foster participation in and generate support for your initiative.

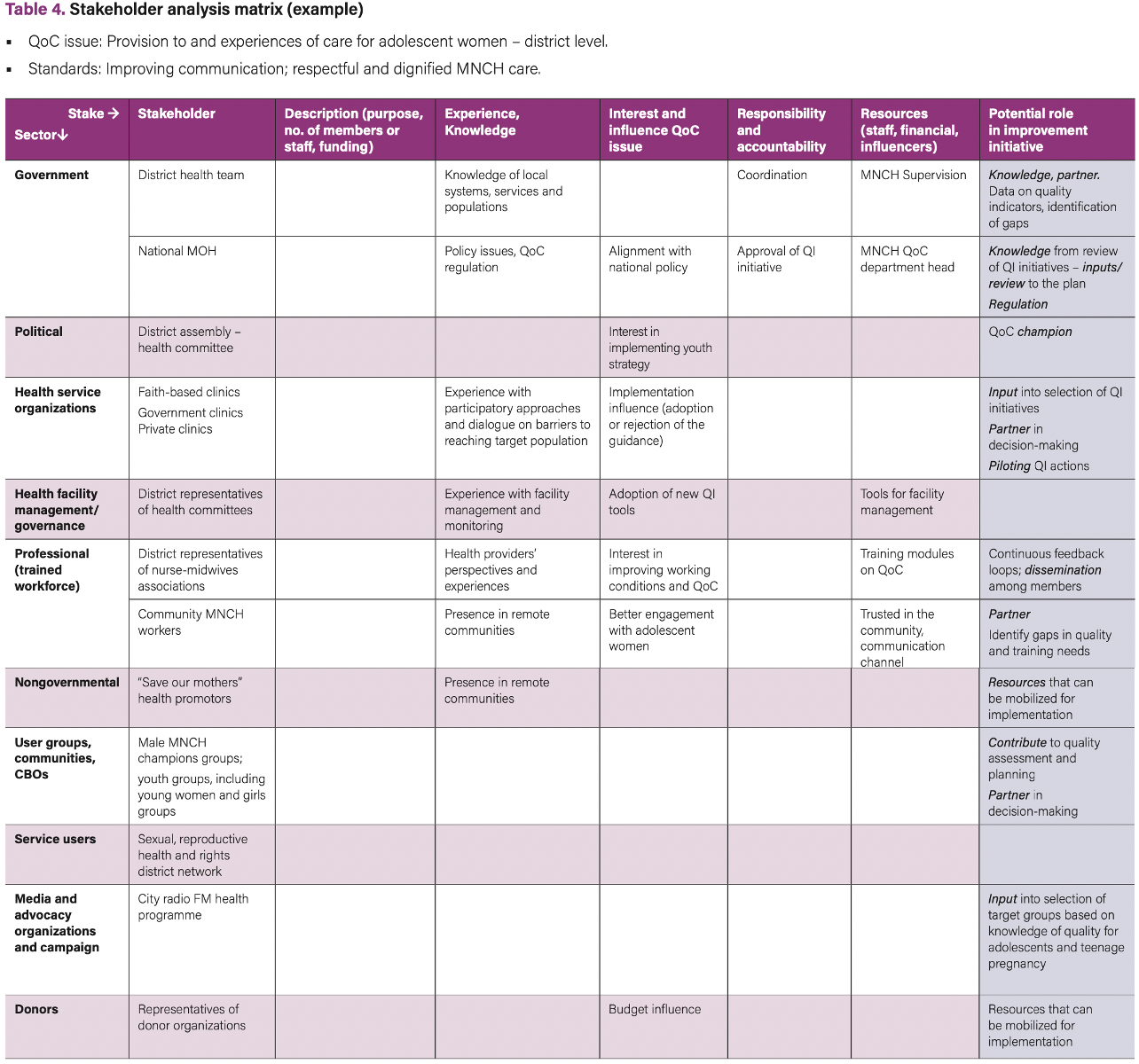

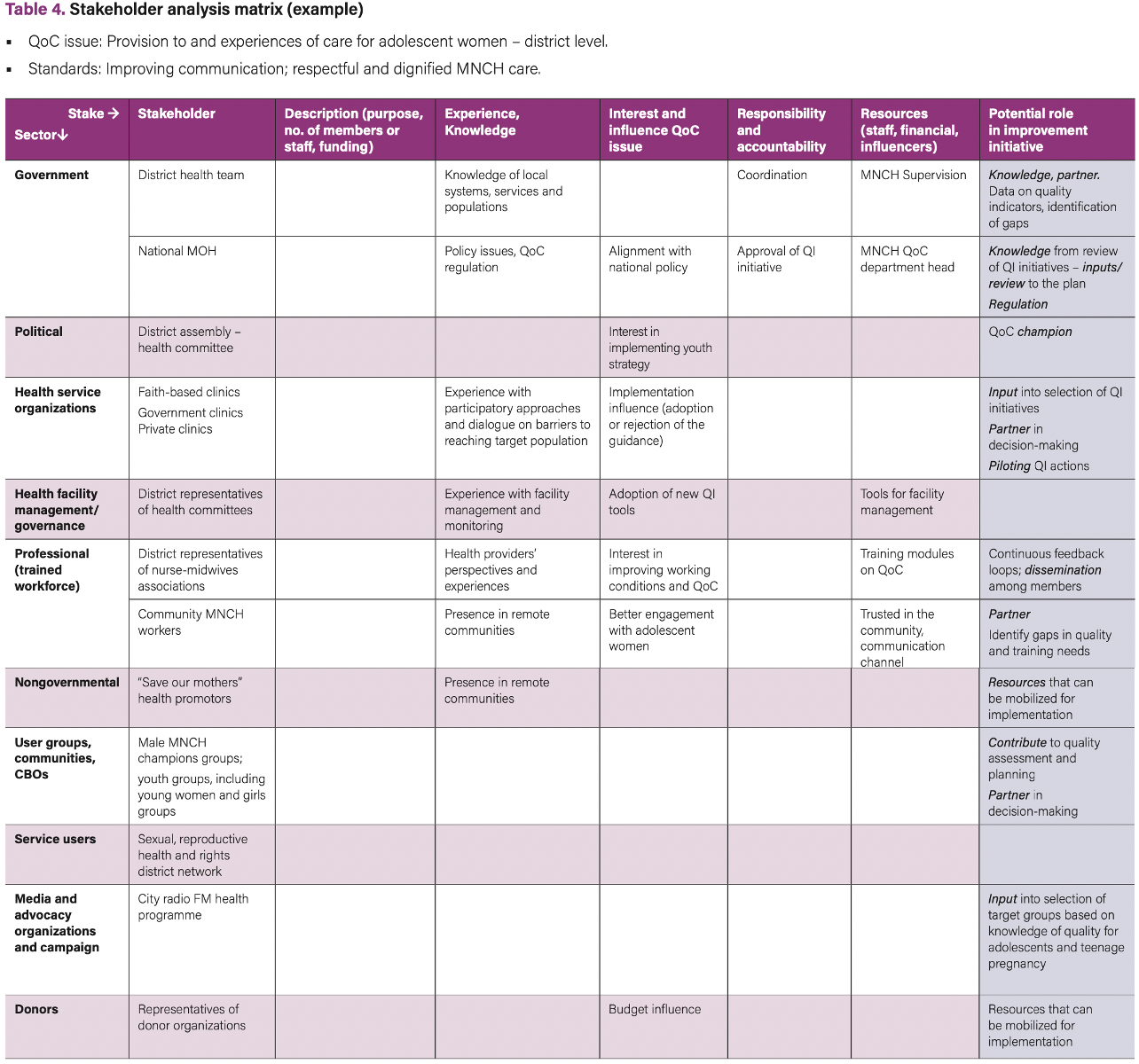

Table 4 provides an example of a stakeholder analysis at the district level which aims to identify stakeholders that should be engaged in defining improvement activities to enhance experience of care for adolescent women. This table can be used as a template.

Activity 4. Identify stakeholders’ potential active role in the QI initiative

In the last column of Table 4, the potential role of stakeholders can be identified. Examples of roles are: partner in the QI team (needs to be involved in decision-making), influence/advocacy champion, informant, funder, knowledge provider, regulator, reviewer, expert consultant, beneficiary, etc.

Box 2 contains a list of resources that can be used for stakeholder and community mapping and analysis.

Box 2. Resources supporting stakeholder and community mapping and analysis

Tools and references for stakeholder mapping and analysis – national and district level

Tools and references for stakeholder mapping and analysis – facility level

Facility and community level

Step 2. Establishing a Quality Improvement governance structure

The stakeholder analysis will have facilitated the identification of core stakeholders that need to be actively involved in the QI initiative. This next step helps to identify the forums in which these stakeholders can be engaged and through which governance mechanism they will be enabled to contribute and provide input in decision-making.

Activity 5. Conduct exploratory interviews

Review the information entered into the stakeholder analysis table and discuss the relative priority of stakeholders to involve in the QI initiative. Exploratory interviews with key stakeholders from different sectors can help confirm their interest and gather input for the engagement strategy. Such consultation can help to further specify the objectives of stakeholder and community engagement in QoC in MNCH. The interviews can also ask the previously identified relevant stakeholders how they would prefer to be engaged as core members of the QI governance structure. Exploratory interviews can cover questions such as:

The earlier in the process people are consulted and listened to, the more likely they are to be supportive and to contribute. Hence, such interviews also help to build stakeholder support in the early stages, even if the stakeholders do not become part of the governance structure. As already mentioned, it is important to take additional measures to ensure women’s voices and vulnerable groups are not overlooked in these consultations.

Box 3 lists resources identified to support the establishment of a governance structure.

Activity 6. Identify the governance structure

A group or a team that oversees a plan, project or intervention can go by a number of names which are often used interchangeably: task force, QI team, quality committee, oversight group, coordination team, etc. The QOC Network implementation guide (32) refers to QI teams as “the focal point for working on specific improvement aims”. Smaller facilities may have one QI team that works on different MNCH aims. Larger facilities may have multiple QI teams. Sometimes, QI teams may exist but lack an MNCH focal person or committee. At the national level, the guide refers to technical working groups (TWG). Many district health systems will already have an existing MNCH TWG that can be a good platform to start establishing a partnership. It will usually be necessary, however, to review the composition of any existing district platform to ensure participation by relevant partners and community stakeholders.

Decision-making on the composition and functioning of the governance structure depends on:

For the QI governance structure, there needs to be enough people to perform the roles, but not so many as to make collaboration impractical. Implementation (TWG, QI) teams usually consist of 8–10 members, while an advisory body or steering committee may consist of a broader set of stakeholders up to 20 members. The composition of the team is not fixed and will change depending on the focus of the partnership (whether focusing on developing a holistic QI plan for MNCH or on sub-aspects of QoC) and the selected QI aim.

Stakeholders can be engaged as:

Criteria for QI team membership.

Ideally, QI team members are:

There may be stakeholders who cannot be directly engaged as QoC team members or members of advisory boards, but who need to be involved at different moments because they can make a particular contribution. Such stakeholders can be engaged as:

- audience receiving the information

- resource person, expert, reviewer

- participant in a focus group discussion

- participant in a stakeholder meeting

- participant of a working group (e.g. on quality assessment, audit and review of stillbirths and neonatal deaths).

Activity 7. Develop partnership agreements

Ideally, identified stakeholders are involved in establishing the roles and procedures of QI teams, TWG or advisory boards. They need an understanding of the process that they are being invited to join, what is required from them, and how long it is going to take, before they will commit to taking part. A start-up workshop can help to clarify expectations and questions, and begin engaging stakeholders in co-developing collaboration principles and establishing processes of communication, coordination, decision-making and leadership. It is recommended that partnership agreements – or more specifically, QI team Terms of Reference – are jointly drafted. Box 3 describes the resources available for supporting the establishment of a governance structure.

Box 3. Resources supporting the establishment of a governance structure

Tools and references for establishing a governance structure

- WHO (2017). Guidance on establishing district QOC teams or coordinating mechanisms (WHO guide for individuals, families and communities [IFC], section 3.4).

- UNICEF (2016). Every Mother Every Newborn (EMEN) quality Improvement guide for health facility st

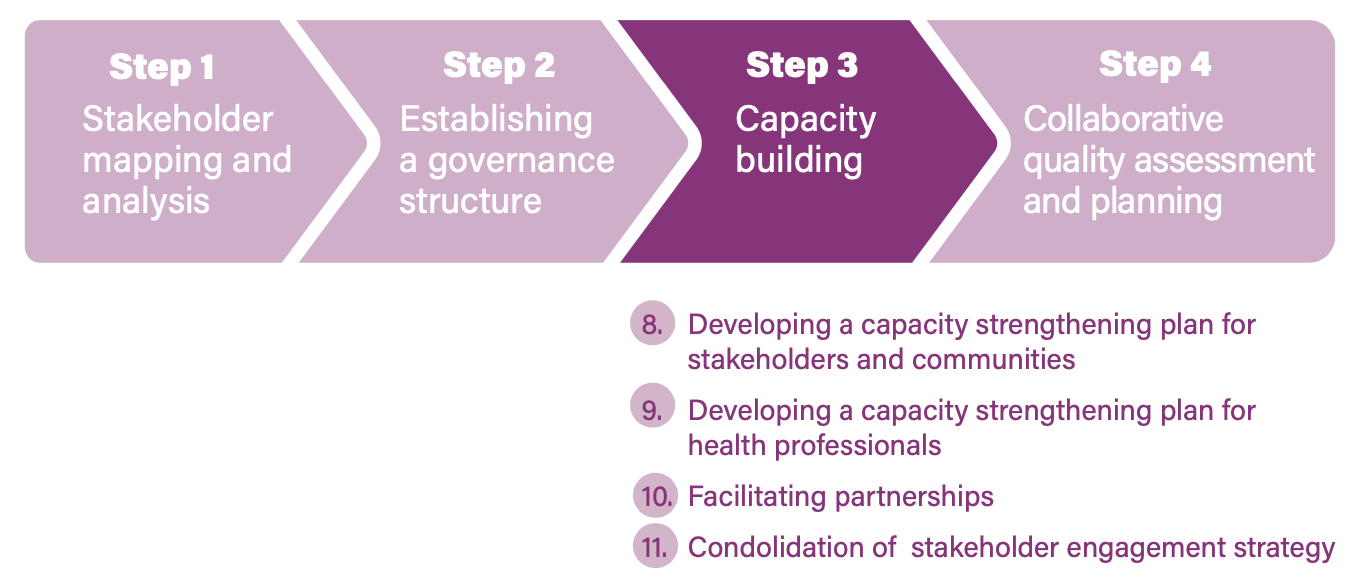

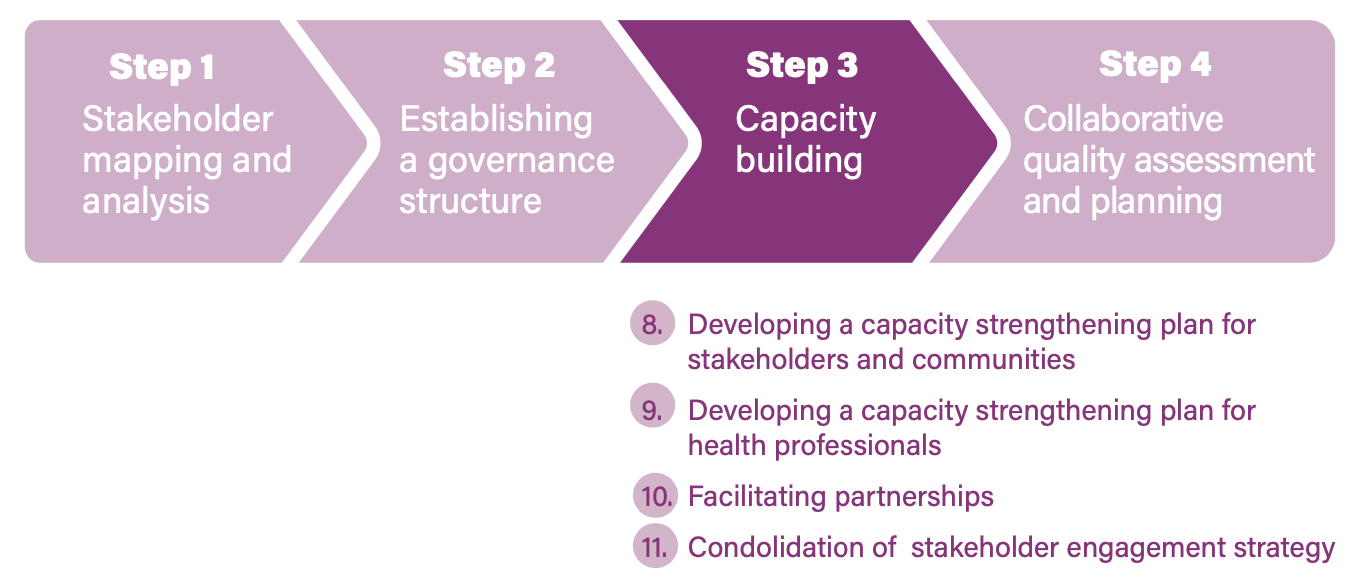

Step 3. Capacity-building and coordination of training programmes

The implementation guide suggests several actions to foster a positive environment for improving QoC. From the perspective of stakeholder and community engagement, this translates to actions aimed at strengthening the capacities and ability of stakeholders, communities and providers to engage with each other and work in partnership in the QI initiative in MNCH.

Activity 8. Develop a capacity strengthening plan for stakeholders and communities

In order for partners in a QI initiative – such as representatives of women, their families and the communities – to be effectively involved, they will need certain capabilities that facilitate their interaction with health providers and managers, and that also increase their ability to understand, participate in, and influence QI processes. Some community members may already have skills and experiences in these processes; others may not. Building these capabilities requires time and commitment, and the related activities need to be included in the QI initiative. Specific capabilities will also be contextually defined and may differ between the “core” stakeholders (active partners in the QI team) and stakeholder and communities in a broader sense. Equally important is building the capacities of community and civil society structures to understand quality issues and to monitor QoC.

Activity 9. Develop capacity strengthening of health professionals

Formal sector health professionals play a key role in facilitating the process of stakeholder and community engagement in QI initiatives in MNCH. To fulfil these roles effectively and to create productive partnerships at different levels, health managers and providers must develop engagement capacities including strengthened interpersonal communication skills. Specifically, they require the skills to:

- communicate with different stakeholders and members of the community and establish relationships with people, including with community leaders, women’s groups, marginalized groups and health workers;

- listen well and learn from the stakeholders and the community;

- share skills and experiences with the community;

- respect people’s ideas and skills;

- promote equity in male–female representation and in representation of the various social, economic and age groups in local decision-making bodies;

- be aware of and respect the social practices, traditions and culture of the community;

- foster collaboration with other projects, organizations and services; and

- promote a holistic or integrated approach to QoC in MNCH (integrating dimensions of provision and experience of care, as well as intersectoral aspects).

It is important to view health professionals not only as facilitators of the QI process but important stakeholders in the process. Health providers will provide important views on barriers to achieving quality care and what support and systems are needed.

Activity 10. Facilitate partnerships

In a number of QI initiatives, collaboration between health facility management, providers, stakeholders and communities will be a new experience. Working in partnership involves listening to different perspectives and managing varying power dynamics. Skilled facilitators are needed to make sure partners can participate and contribute effectively. Facilitators need to guide partners in the processes of:

- shared assessment and analysis of the situation;

- the design of context-specific approaches;

- shared agenda setting and planning;

- defining roles and responsibilities. (33)

Within the QI team there may be someone with the necessary skills, or an external facilitator or coach may be involved, in particular, at the start-up phase when the QI teams or groups are set up, but also during QI team planning and M&E meetings. A facilitator may use team-building exercises to develop the partnership at different stages. Abilities a facilitator needs to possess are: knowing how to ask clarifying questions; active listening; being able to encourage everyone to share; relating discussions to people’s realities; and managing differences of opinion. (34)

The district and national levels have a role in facilitating stakeholders, communities, health authorities and providers to engage in a partnership. An important requirement is the training of the health workforce as well as community representatives in skills and capacities to effectively communicate, listen, and engage in joint decision-making and planning. If multiple facilities participate in the QI initiative, districts can explore efficient ways of building capacities in collaboration with other district-level organizations.

Activity 11. Consolidate the stakeholder and community engagement strategy

If there is an existing national/district/facility operational plan for improving MNCH QoC, the stakeholder and community engagement strategy and governance structure should be integrated. The engagement plan is flexible and should be reviewed at various points throughout the programme. The engagement strategy should identify who is responsible for this as well as for coordinating stakeholder engagement at different levels (facility, district or national level). Determine who in the TWG (national level) or QI team (district and facility level) can oversee the plan implementation and review. Box 4 lists the resources that can be used to support capacity strengthening.

Box 4. Resources supporting capacity strengthening

Tools and references for capacity-building and empowerment of communities

- Identification of needs and available community resources through focus group discussions and preparation of user-friendly information packages on MNCH quality policies, quality measures and indicators and facility processes.

- Learning Network (2014): Health committee learning circles. Increasing understanding of National Core Standards, the importance of quality health care, and how clinic health committees can participate in standards of QoC, responsibilities and QI plans.

- World Vision International (2016): Capacity-building of health-focused community groups that are empowered to coordinate and manage activities leading to improved overall community health and strengthened civil society.

- Health facilities can make visible and accessible the rights of women and children and the responsibility of the health facility in providing MNCH, as well as display important information on health facilities, such as services provided, hours of operation, staff timetables, and fees for services (if any). Example: Display of patients’ and/or health workers’ charter or other charters such as the Charter on Respectful Maternity Care, including the Seven Universal Rights of Childbearing Women.

Tools and references for enhanced access to information and capacity-building of health professionals

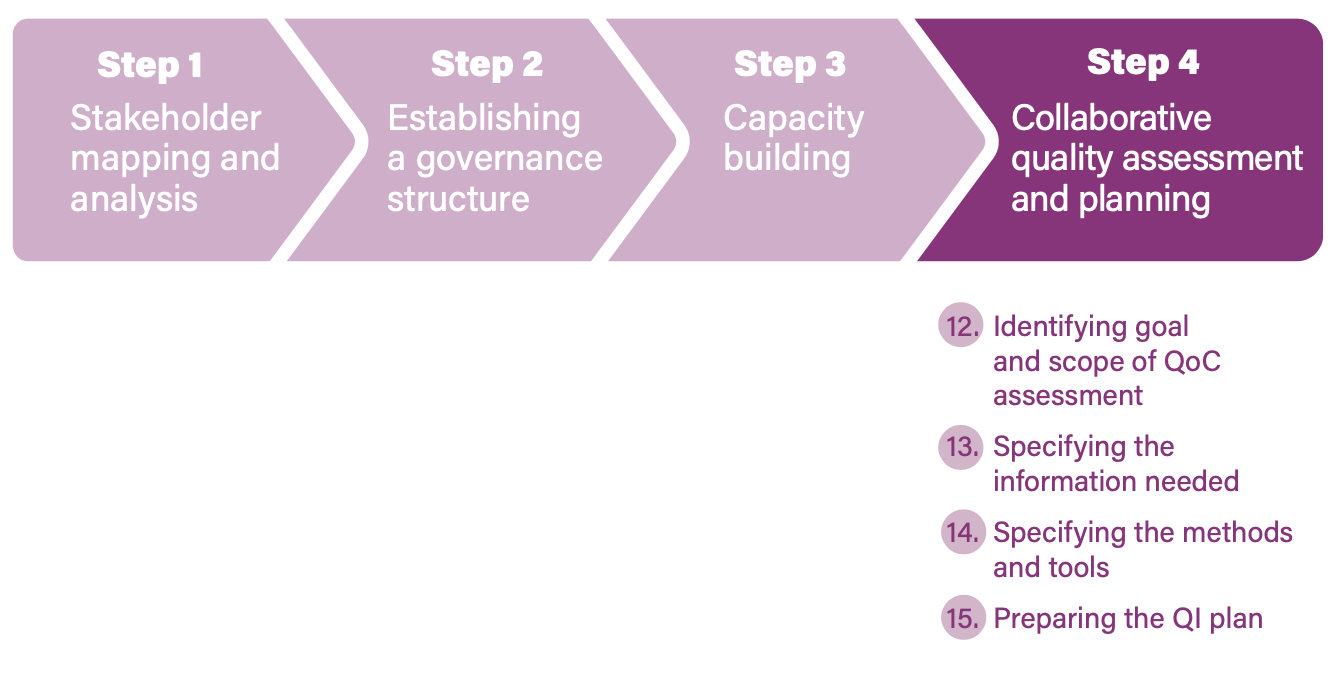

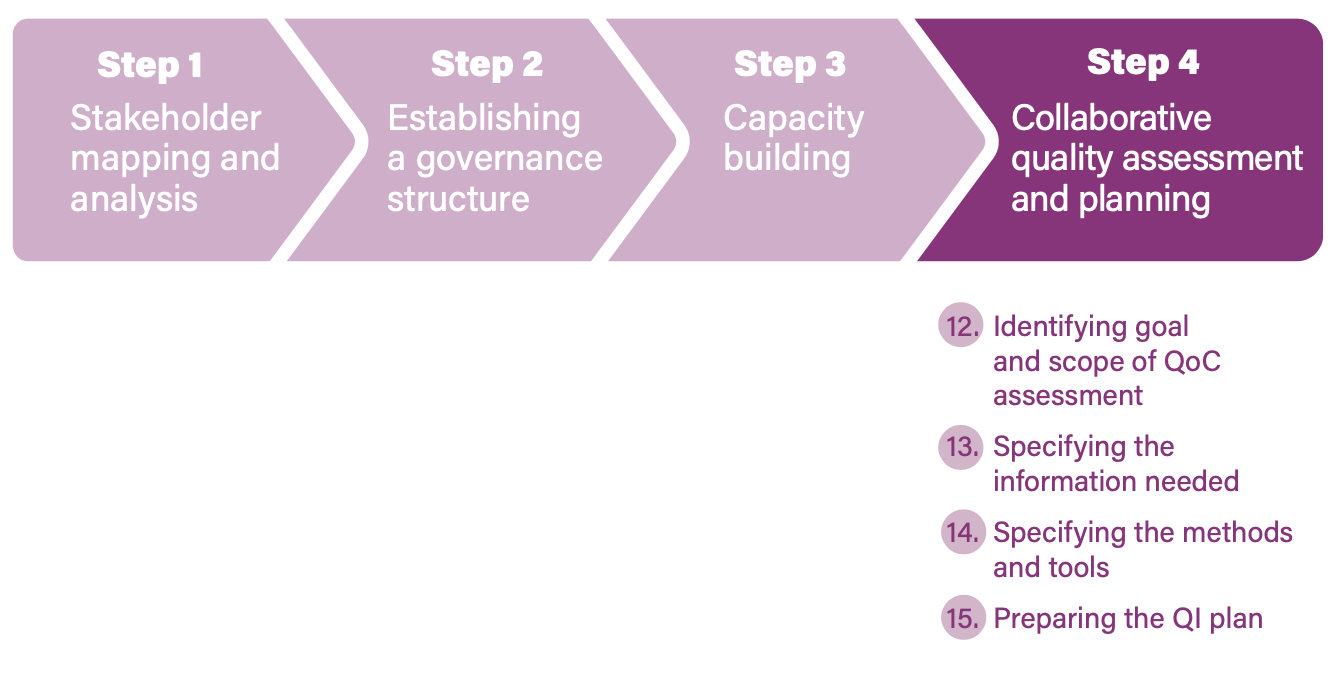

Step 4. Collaborative quality assessment and comprehensive Quality of Care planning

After having defined the governance structure and QI team composition and procedures, the next step is to conduct a collaborative quality assessment to identify gaps and improvement aims. Such assessments provide an opportunity to collect, aggregate and compare data on all dimensions of QoC and to develop a comprehensive operational plan. This step describes activities for the district and facility levels.

After having defined the governance structure and QI team composition and procedures, the next step is to conduct a collaborative quality assessment to identify gaps and improvement aims. Such assessments provide an opportunity to collect, aggregate and compare data on all dimensions of QoC and to develop a comprehensive operational plan. This step describes activities for the district and facility levels.

What are collaborative quality assessments?

Collaborative quality assessments are approaches in which different groups (service users, marginalized groups, health providers, managers, etc.) evaluate the QoC; for example, through the use of rating methods (scorecards, checklist with a grading scale) or group discussions. The criteria for quality are first defined separately by the groups or sub QI teams. This is followed by an interface meeting where the groups jointly review the criteria and results, compare different perspectives and identify improvement aims. Out of this assessment, the core group (QI team) prepares a QI plan.

Besides identifying improvement aims, a collaborative quality assessment is an important strategy for community and stakeholder engagement that can achieve multiple additional goals: enhance transparency and mutual understanding; mobilize relevant support for a QI initiative; encourage acceptable and respectful MNCH services; improve experiences of care; increase accountability to service users; and empower health providers, communities, families and women in the longer term. Such an assessment is usually led by the QI team but may involve the delegation of particular assessment areas to sub-teams or groups.

As observed by the QOC Network, certain areas of quality assessment remain undeveloped, particularly with regard to experience of care. (35) Many QI teams may be new to assessments of processes of care from the perspectives of women and communities, and to identifying improvement initiatives focusing on experiences of care. Also, many assessment methods overlook health workers’ perspectives of QoC. While there are many assessment and problem analysis methods, this section focuses on community-based monitoring, tools for collecting women’s perspective on and experiences of care, and methods to assess health providers’ perspectives on QoC.

Activity 12. Identify the goal and scope of collecting perspectives from communities, women and health providers (36)

The specific goal identified for capturing the QoC perspectives and experiences of communities, women and health providers is what determines the methods used to collect information, report findings and make improvements. In the planning phase, discuss the following questions:

- What guidelines exist and which actors have experience related to collecting information on experiences of care of communities, women and health providers?

- Why do we collect information about views of QoC from communities, women and health providers? Is it for information (understanding experiences of care), involvement (identifying opportunities for QI) or collaboration ( joint planning and implementation of QI initiatives)?

- How might the assessment itself also contribute to capacity strengthening, empowerment and accountability?

- What organizational level are we considering: health clinics, outreach services, maternal health clinics, individual health workers, teams, particular services (such as antenatal care, vaccines, etc.)?

Activity 13. Specify the information needed

It is important to review what information already exists and to identify where the gaps are before collecting additional information:

Activity 14. Specify the methods and tools

While considering which method to use to gather information, also think about who will be gathering the information and their respective skills; different methods are associated with different levels of engagement: information, involvement, or collaboration. A combination of methods is likely to achieve multiple objectives. Some factors to bear in mind are:

- Consider whether the assessment is for planning purposes only or for ongoing feedback (i.e. can the assessment be used for subsequent collection of feedback).

- The quality assessment must be appropriate for finding areas of improvement and potentially for keeping track of improvements. The type of data and questions to be addressed should determine the data collection methods. These include:

- methods that do not require interaction (e.g. surveys, questionnaires, suggestion boxes);

- methods that allow for gathering of more in-depth information on the what, how and why of experiences (e.g. in depth-interviews);

- methods that allow interaction between members of the same group (e.g. women, health providers) or participants (e.g. focus group discussions, discussion forum).

For such assessments to be meaningful for health providers, women and communities, they have to go beyond one-off events. Identify methods to bring together data from the individual assessments (e.g. interface meetings, stakeholder meetings) and to facilitate continued interaction. Community-based monitoring and social accountability approaches support such interactions (see Box 5).

Activity 15. Prepare the QI plan

The QoC team can use the outcomes of collaborative quality assessments to design or finalize the QI plan, with regular feedback to participants of the assessment. The QoC team uses the data from all groups to identify the gaps, improvement aims, and approaches and actions that are appropriate to solve the identified gaps in the short term and in the long term. QoC teams should also keep an open mind and try new things if they learn about other successful strategies to improve care, including strategies to improve experiences of care (see Box 5 for examples). Further guidance on developing QI operational plans is provided in detail in several guidelines for different levels. (37)

Box 5. Resources supporting collaborative quality assessments

Tools and references for partnership-led quality assessment and QI planning

Partnership-led quality assessment and improvement planning (QoC in general):

- Save the Children (2003). Partnership defined quality: a toolbook for community and health provider collaboration for quality improvement.

- Quality of Care Network (2017). Monitoring framework proposes measurements to assess all aspects of quality of MNCH care.

-

WHO (2017). WHO IFC Toolkit. Participatory community assessment (PCA) is a tool that district health services can use to assess the maternal and newborn health (MNH) situation and needs in a participatory manner, through collaboration within the health sector and with other sectors (such as education and transport), with district authorities, NGOs, religious organizations and other community groups. Using the results of the PCA, partners can then plan actions together to help create an enabling environment for care of the mother and newborn in the home and in the community, and to increase access to quality MNH services.

Maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response with community engagement components:

- Bayley et al. (2015). Community-linked maternal death review (CLMDR): An assessment of the value of involving communities in investigating and responding to local maternal deaths. Collaborative analysis resulted in the development of community-planned actions, district hospital and health centre actions.

- Biswas et al. (2018). Social autopsy for maternal and perinatal deaths: A tool for community dialogue and decision-making. A tool to engage family members of the deceased, senior community members, community leaders, religious leaders, teachers, and members from the local government.

Tools and references for community-based monitoring and social accountability

- Tools such as community scorecards and maternal health report cards may facilitate community–provider collaboration, and relevant data can be used by districts for planning purposes as well as for engaging stakeholders at the district level; for example, through organizing district-level public hearings or through the publication of aggregated analysis and organizing district feedback meetings.

- CARE (2013). Tools to enhance provider accountability by using community-driven assessment and monitoring: The Community Score Card (CSC): A generic guide to implementing CARE’s Community Score Card process to improve quality of services.

- World Vision International. Citizen Voice & Action field guide developed by World Vision International.

Tools and references for the assessment of health provider perspectives on quality of care

- Save the Children. Health worker defined quality. Exercises to be conducted in a 1- to 2-day workshop (PDQ-Youth guide, pp. 30–35).

- Merriel et al. (2018). Ten low-cost recommendations to improve working lives of maternity health-care workers, based on a case study in Malawi.

Tools and references to assess women’s experiences of care

Examples of QI initiatives focusing on experiences of care:

Endnotes

-

Stakeholder engagement tool. Chapel Hill: Measure Evaluation; 2011 (https://www.measureevaluation.org/resources/publications/ ms-11-46-e).

-

Standards for improving quality of maternal and newborn care in health facilities (p. 16).

-

Handbook for national quality policy and strategy.

-

Handbook for national quality policy and strategy (p27).

-

For example: Guidelines for governance and management structures. Kampala: Republic of Uganda Ministry of Health; 2013 (http://www.health.go.ug/docs/GMS.pdf )

-

Implementation guide for facility, district and national levels

-

WHO community engagement framework for quality, people-centred and resilient health services. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017 (https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/259280/WHO-HIS-SDS-2017.15-eng.pdf).

-

Partnership defined quality for youth: A process manual for improving reproductive health services through youth-provider collaboration. Washington (DC): Save the Children; 2008 (https://www.savethechildren.org/content/dam/global/reports/health- and-nutrition/pdq-y-manual.pdf ).

-

Implementation guide for improving quality of care for maternal newborn and child health. Working document. Lilongwe: Network for improving quality of care for maternal newborn and child health; 2017 (https://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/topics/ quality-of-care/quality-of-care-brief-implementation.pdf). See also: Handbook for national quality policy and strategy.

-

National Quality and Risk Managers Group. Guide for developing a consumer experience framework. Wellington: Health Quality and Safety Commission; 2012.

-

For example:

Implementation guide for facility, district and national levels and A mapping and synthesis of tools for stakeholder and community engagement in quality improvement processes for Sexual, Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn and Child Health - forthcoming,

CQI for respectful maternity (Ethiopia)

Implementation guide for improving quality of care for maternal newborn and child health

Handbook for national quality policy and strategy.Implementation guide for improving quality of care for maternal newborn and child health. (Working document.)

Handbook for national quality policy and strategy: a practical approach for developing policy and strategy to improve quality of care. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018.

Stakeholder mapping and analysis is often done informally, in an ad hoc way, and not systematically updated. As a result, it may only include stakeholders who already agree with the policy or programme or only invite participants from selected organizations that are directly involved in the implementation. Such approaches may miss important interest groups that could contribute valuable insights, influence or resources to the programme. Omitting their voices may threaten the embedding and sustainability of the programme. (27)

Stakeholder mapping and analysis is often done informally, in an ad hoc way, and not systematically updated. As a result, it may only include stakeholders who already agree with the policy or programme or only invite participants from selected organizations that are directly involved in the implementation. Such approaches may miss important interest groups that could contribute valuable insights, influence or resources to the programme. Omitting their voices may threaten the embedding and sustainability of the programme. (27) The quality issue at stake may be informed by existing quality assessments or may be predefined by the improvement aims set by national-level QoC policies. When there is an opportunity to conduct a new or more comprehensive (i.e. addressing all dimensions of QoC) quality assessment at national, district, or facility level, this could become a stakeholder and community engagement process in itself. Guidance on such processes is provided in Section 3.

The quality issue at stake may be informed by existing quality assessments or may be predefined by the improvement aims set by national-level QoC policies. When there is an opportunity to conduct a new or more comprehensive (i.e. addressing all dimensions of QoC) quality assessment at national, district, or facility level, this could become a stakeholder and community engagement process in itself. Guidance on such processes is provided in Section 3.

After having defined the governance structure and QI team composition and procedures, the next step is to conduct a collaborative quality assessment to identify gaps and improvement aims. Such assessments provide an opportunity to collect, aggregate and compare data on all dimensions of QoC and to develop a comprehensive operational plan. This step describes activities for the district and facility levels.

After having defined the governance structure and QI team composition and procedures, the next step is to conduct a collaborative quality assessment to identify gaps and improvement aims. Such assessments provide an opportunity to collect, aggregate and compare data on all dimensions of QoC and to develop a comprehensive operational plan. This step describes activities for the district and facility levels.

Next Chapter

Next Chapter